Clinical care only accounts for a small part—an estimated 10 to 20 percent—of the factors that affect population health. The rest is determined by social, behavioral, and environmental factors, such as education, housing, and income, which interact dynamically to shape people’s health and well-being. These factors, which are sometimes called social determinants of health, play such an outsized role in keeping people healthy that a growing number of leaders in the government, philanthropic, nonprofit, and private-sector health care communities believe it is critical for providers to address them.

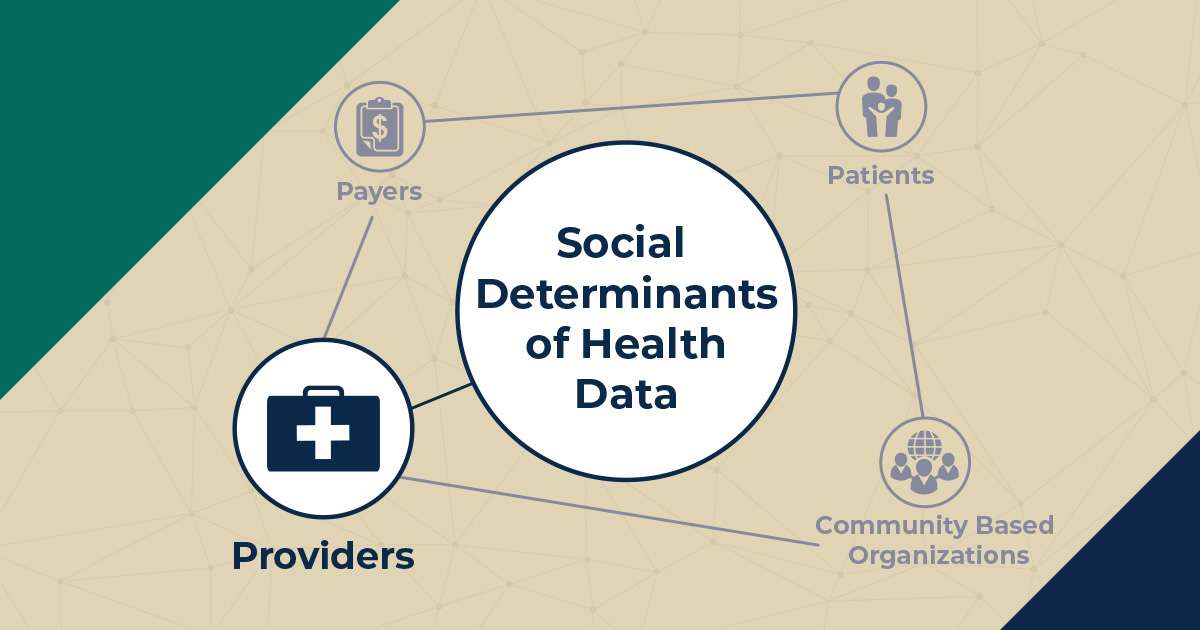

To improve patients’ overall health and well-being, we need better information about social determinants of health and the best ways to tackle them. This blog post is the third in a series that explores the needs, challenges, and opportunities related to collecting and using social determinants of health data to drive decisions in health care delivery and payment. Each post will examine these questions from the perspective of a different stakeholder group involved in such decision making. Click here to read the post introducing this blog series.

This post describes how health care systems and providers have been—and can be—critical partners in collecting and acting on social determinants of health data.

Health care providers have long understood that identifying the causes of patients’ health issues is vital to treating and preventing disease. Social needs are the predominant influencers of health, so gathering data on a patient’s social needs is as important, or perhaps more so, than the information providers already collect on current and past medical conditions and clinical risk factors. Health care providers are in an ideal position to ask patients about their social needs and should look beyond the clinical realm to inform shared decision making and develop so-called whole-person care plans.

By practicing social prescribing—using clinical interactions to make referrals to community resources that address a patient’s priority social needs—providers can serve as gateways for patients to resolve their nonmedical challenges, increasing patients’ ability to follow clinical recommendations and improve their quality of life. Collecting data on individual social needs through systematic screening allows providers to diagnose social needs; develop a greater understanding of the circumstances, values, and preferences of each patient; and better meet, or treat, patients’ needs by offering the right care, services, and referrals.

For example, under the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation’s Accountable Health Communities (AHC) Model, Mathematica is helping more than two dozen organizations bridge the gap between clinical care and community services. These organizations universally screen for social determinants of health in clinical sites, referring patients with identified needs to appropriate community service providers and offering AHC navigators to connect patients to relevant resources.

Trained staff in any clinical setting can efficiently administer a validated social determinants of health screening tool to collect data. Documenting and integrating these data into the patient’s electronic health record (EHR) facilitates data sharing with other clinicians on the patient’s care team to improve care coordination. While many hospitals already screen inpatients for some social needs, consistent EHR documentation of social determinants of health data would allow hospitals, health systems, and payers to quantify, track, and develop initiatives to address patients’ nonmedical challenges.

Health care systems and providers can leverage their aggregate data on social needs and social prescribing. With those data, they could more accurately assess the risks within their patient populations; advocate for alignment of patients’ social determinants of health risks when negotiating alternative and value-based payments; and help secure sustainable funding for the nonclinical services that improve quality of care, health outcomes, and health equity while reducing health care costs.

Despite the many advantages of collecting and using social determinants of health data, there are significant hurdles to overcome.

- Lack of buy-in. Some health care systems, providers, and staff might not fully buy into the significance of social factors in determining health, or the potential of social prescribing to improve wellness and reduce cost.

- Time constraints. Staff at clinical sites might be stretched thin and feel that they don’t have time to add another task. Those who lack the bandwidth to directly address patients’ social needs might be hesitant to implement social determinants of health screening.

- Inconsistent data collection efforts. Health care systems and providers that incorporate social determinants of health into their practices are largely doing so on an ad hoc basis. Although there are validated tools to screen for social determinants of health, there is no consensus on a uniform approach to collect and use these data. Social determinants of health data recording is inconsistent as well. Some health care providers have incorporated social determinants of health screening and documentation into their EHRs; some partner with vendors or use customized social determinants of health data systems; others do not collect or record these data at all.

- Data sharing restrictions. Even when health care providers use EHRs to collect social determinants of health data, their ability to share this information with other health care systems, patients, payers, or community-based organizations is restricted. This lack of interoperability (that is, the ability of different health information systems to share and collaboratively use data to improve individual and population health) poses a challenge to the portability of all health data, but is particularly challenging for social determinants of health given the inconsistency in collected data and the broader network with which such data can be shared. Concerns about protecting patients’ privacy might also impede the development of data sharing systems and processes.

In their direct patient-facing role, health care providers have the unique opportunity to recognize, document, and address the social factors that impede individual and population health. To seize this opportunity, there are several strategies providers can use to leverage social determinants of health data and play a key role in moving the needle toward health improvement.

- Commit to universal screening. It’s important that health care providers proactively collect data on all patients’ social needs in a way that is unified and collaborative. As part of the data collection process, health care providers need to partner with one another, patients, and other stakeholders to build consensus around common validated measures. Enhancing patients’ comfort level and willingness to disclose the social factors influencing their health requires providers to strengthen trusting relationships and cultivate cultural humility. Health care providers should engage patients and community service providers to collaboratively develop and integrate standard processes (adaptable to each site’s workflow) to collect and protect social determinants of health data. Several efforts are underway to improve alignment and sharing in key areas, including documentation. The Social Interventions Research and Evaluation Network’s (SIREN) Gravity Project convenes stakeholders to facilitate planning for interoperable electronic health information exchange. In addition, the new proposed rules for EHR interoperability, put forth by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and supported by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, promote seamless access to individual health information for patients and providers.

- Harness and expand existing EHR tools. EHRs can effectively incorporate social determinants of health screening questions and reminders, and flag priority issues. Building EHR capacity to support electronic communication across the clinical and nonclinical care continuum will facilitate social prescribing, close the loop on referrals, and, most importantly, support shared decision making and realistic treatment planning. Health care systems and providers should take advantage of the ICD-10 codes that identify psychosocial and socioeconomic factors to aggregate and track patients’ nonmedical challenges. Various types of staff can gather and document information to support codes Z55-Z65. Routine use of these codes would greatly increase the pool of social determinants of health data that hospitals, health systems, or payers can use to develop health improvement initiatives. Providers should be on the lookout for the two dozen additional proposed ICD-10 codes that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention will consider for potential implementation in 2020.

- Educate and train staff on social determinants of health. Understanding the important role social circumstances play in determining health can foster support and develop champions of this work at all levels. Although definitive demonstrations of improved health outcomes and reduced costs are limited, sharing practice-level social determinants of health data and patient success stories with staff demonstrates progress, increases buy-in, and motivates behavioral change. Implementation and effectiveness data are beginning to emerge, and federal, state, and community health center–level studies are underway.

- Cultivate partnerships with community-based organizations (CBOs). Partnering with CBOs either directly or indirectly (such as through a social worker or hospital community benefits program) facilitates treatment of the root causes of and contributors to illness through social prescribing. These partnerships also open the door to bidirectional data sharing to initiate and pursue CBO referrals that support clinical decision making. Health systems and providers do not need to reinvent the wheel to do this. They can collaborate with CBOs to create direct links between their data systems; build an EHR-based CBO list that auto-generates referrals; or consult an existing community resource inventory database, such as a local 2-1-1 directory. As my colleagues described in a previous post, health care systems and providers can leverage existing relationships and create new partnerships with CBOs, building strong cross-sector bridges that promote data sharing to improve whole-person care coordination.

Full adoption of a data-driven paradigm that recognizes and integrates social needs, embraces whole-person care, reduces providers’ financial risk, decreases health care costs, and improves individual and population health requires a cultural shift in the health care and social services sectors that each have their own language and customs. Unconventional, cross-sector partnerships between health care, social service, payer, and policy sectors—that include the patient’s voice—strengthen the ability of each sector to address social needs, improve health and well-being, and potentially demonstrate the business case for using social determinants of health data. Health care systems and providers have the opportunity to step up and collaborate to gather and leverage social determinants of health data to tackle the upstream factors that influence health.

Read other posts in this series:

- Lost in Translation: The Importance of Social Determinants of Health Data from the Patient Perspective

- The Power of a Data-Informed Partnership: Working with Community-Based Organizations to Address Social Determinants of Health

- To Address the Social Determinants of Health, Start with the Data

- In Pursuit of Value: How Payers Can Leverage Social Determinants of Health Data to Improve Outcomes